Wednesday, November 16, 2011

Monday, October 10, 2011

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Cromity and Day: United by Music by Lani Conway

Dennis Day (left) and Steve Cromity (right) performed a 9/11 tribute concert at last night at Two Steps Down. Credit Lani Conway

Cromity and Day after filming a scene on the Brooklyn Bridge for "Unfinished Business," a 9/11 film documentary produced by Day Credit Lani Conway

Add your photos & videos

Though they shared a bond forged during the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, Fort Greene resident Steve Cromity and Dennis Day didn't actually meet until six years later—and then only by chance at a New York vocal competition.

But last night at Two Steps Down in Fort Greene, the two musicians were once again reunited to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attacks on Sunday.

“No more time for fear, I know where I’m going,” Cromity sang to a packed house in the upstairs room of the Dekalb Avenue restaurant.

Ten years ago, Cromity would have told a different story.

On Sept. 11, no one at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey knew Cromity was also an aspiring jazz singer when he went to work that fateful morning. The night before, Cromity, who was the manager of construction in the bi-state agency's engineering department, had been out late. He had spent the night jamming at a Long Island bar like he did every Monday, but still managed to make it on time from his Queens home to his early morning meeting.

On the 73rd floor of his boss’s office, Cromity stared out the window, noting the clear view of the Statue of Liberty and the blue waters of the Hudson River. Suddenly, a tremendous jolt sent the building into a violent swing that nearly knocked Cromity to his feet.

American Airlines Flight 11 had struck the north tower of the World Trade Center twenty floors above, clouding his perfect view with a shower of ash and smoke. The singer who found inspiration in jazz vocalists like Eddie Jefferson, filed down the stairs with the rest of the staff, encouraging firefighters as they ascended past him with their pounds of equipment and into a “no escape situation.”

Below, a few blocks from the building, Dennis Day, gazed up at the north tower’s smoking hole, clutching the hand of a woman whose son worked on the 104th floor. Moments ago, she was frantic, crying out to anyone who would help.

When the first plane struck, Day, who was also a part-time singer, was on his way from Upper Manhattan to his office at the New York Division of Housing and Community Renewal on Beaver Street. He was still holding the mother’s hand when the second plane hit. Day and the woman started to run.

It was then that Day began to question his life’s purpose.

“As I was escaping, something told me that if I get out of this, I should change my trajectory,” he said. “I instantly made the decision to focus on singing, music, composing and developing as a musician and artist.”

Six years later, after meeting each other at the vocal competition, the two discovered they had a shared experience via Facebook. “We didn’t know it, but we had more in common than just music,” Cromity said.

According to Cromity, 9/11 served as a motivation to continue developing his musical talents. He started singing on the side a year earlier, but made his talents known with the release of his debut album, “Stepping Out” in 2004. In 2005, Cromity retired.

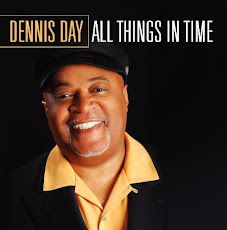

For Day, 9/11 had more of a direct impact. He immediately began to write his own music and enrolled in a media arts master’s program at Long Island University before retiring from his state job in 2006. A year later, he released “All Things in Time,” a collection of interpreted songs by popular jazz greats. Just two months ago, the East Chicago native with a love for blues, doo-wop and rock, performed at his first piano recital.

More recently, Cromity and Day shot a scene from “Unfinished Business,” a film project Day started shortly after Sept. 11 to recount the events and experiences of that day. The scene showed Cromity walking from the Brooklyn side and Day from the Manhattan side of the Brooklyn Bridge. They stopped in the middle of the bridge to reflect on their 9/11 experiences and their music.

Sunday night, amidst the lively crowd’s energetic claps and cheers, Cromity and Day continued that conversation onstage, singing a line from “Don’t Get Scared,” a popular duet by noted vocalese artist, King Pleasure: “When you see danger facing you, little boy don’t get scared.”

“We talked about doing the song because all of us were frightened on that day,” Day said. “It seemed to speak to the whole idea of trying to talk and support one another through a crisis.”

Monday, September 5, 2011

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Archives Reveal Family History

Viewpoints

Gannett Westchester Newspapers Sunday, March 18, 1984 Section B, Page 8

Daily, the National Archives, headquartered in Washington, becomes a beehive of activity. It is a place where tourists gaze into microfilm machines examining census records hoping to connect the branches of their family trees.

An occasional researcher manages to experience the jubilation Alex Haley, author of “Roots,” must have derived in his first association of two clue words, “kamby balongo” (river) and “malonga” (drums”), words passed down to him through stories as told by his African ancestors.

Family histories are often handed down orally and not recorded, so it is rare when the casual tourist does connect the links in his or her family tree. Facts such as county of residence, age, and origin of birth often become distorted so that by the time th serious researcher has assembled useful clues, the processes of gleaning fact from fiction becomes the researcher’s nightmare.

Changes in zoning laws and the names of cities and towns over the years can literally, on paper, displace entire families into different governmental suburbs, towns, villages or counties. Because of dislocations resulting from natural catastrophe, nonuniform census laws and lost census data, only one in 100,000 Americans is able to trace his family origins. The National Archives, located several blocks east of the White House, is a prime source for finding valued volumes of family census and manuscripts.

In 1977 I had written a column for the now-defunct Philadelphia Evening Bulletin that criticized London Times reporter Mark Ottaway’s assertion that Haley’s work was based upon bogus research. Curiosity over my own heritage later would lead me to embark upon a genealogical journey armed with two clues; the name of my great-grandfather, Anderson Day, and the county of Barbour in Alabama. I began.

First, I registered along with the other anxious tourists. I was then given a card that entitles one to conduct research. I came across the Alabama volume and proceeded to seek references to the surname Day.

Hundreds of Days surfaced; all were Caucasian and no blacks were shown. After a conversation with an archives floor supervisor I learned that only free blacks were counted in the Alabama census before 1880, and only those owning property in many cases were even included in 1880 and afterwards until the census laws were reformed.

Now as I reeled through the microfilm, traveling through each of the Alabama counties of 1880, I recalled our family’s brief trips to Phenix City, Alabama, my father’s hometown about which a movie was made entitled “The Phenix City Story.” The film depicted the violence, corruption, and racism in the deep South of the mid 1950’s. There were memories of learning to ride bareback and being baffled by stern parental instruction in proper southern etiquette when found among southern white folk.

The customary, “yes, sir” and “yes, ma’am” apparently were valuable lessons when traveling south for northern black children in the 1950’s. The nostalgia had begun to fade when suddenly the name Anderson Day appeared! Several long distance telephone calls confirmed my finding. But shown among the household reported in the census records was even another black male: Simon Peter Day, 75, relationship to the head of household: father, birthplace: Virginia. Apparently, I had stumbled across an heretofore undisclosed family fact. Patriarch Simon Peter Day had lived with his wife, Julia, 60, and son, Anderson Day, in an extended nuclear family so common in 1880.

By cross referencing census tracts, historical data gathers new information, new births, deaths, marriages, and changes in economic status such as from sharecropper to property holder.

Next, I would spread my search into Virginia, Simon Peter’s birthplace, in search of any references documenting his origins there. By day’s end, I had gone through the Virginia census of 1810 for Fairfax County when I found head of family Simon Peter Day, status: free Negro, servants: two slaves owned.

National Archives supervisors attested to the rarity of my discovery. Only a few free Negroes were even registered in Virginia during this census period. Fairfax County, VA is separated from the District of Columbia by the Potomac. A 1792 law requiring free blacks to register was largely ignored for 20 years, so a number of blacks freed or born free of the estates of George Washington and George Mason, whose Declaration of Rights in the Virginia constitution was an inspiration for the Declaration of Independence, were irregularly recorded.

I found the best theory and clues to my ancestors’ movements in the Fairfax Chronicles, a Virginia history newsletter. By 1782, the number of blacks in Fairfax County was more than 3,600, 41 percent of the population. One hundred eighty-eight of these were owned by Washington and 125 by Mason, whose wealth allowed him leisure time to write his declaration.

The 1782 Virginia emancipation law allowed free blacks to remain in Virginia. Then the 1782 law was amended in 1806. Simon Peter was in his teens. The amended law provided that all newly freed blacks once again were legally required to leave Virginia or risk being sold into slavery.

The incentive to remain free seemed the only reasonable one as I reflected on that memorable day in the archives. Simon Peter Day desired freedom for himself and his family.

Friday, March 18, 2011

Melvin Sparks Allowed His Music to Transcend Race and Religion

Melvin Sparks Allowed His Music to Transcend Race and Religion

I attended the funeral of Melvin Sparks Hassan today, in Mt. Vernon, New York, 20 miles north of Manhattan. Melvin was a devout Muslim. He passed Tuesday, March 15th. suffering a heart attack at home, he was 64 years old.

It was a very interesting learning experience for non-Muslims like me. I learned about some aspects of the Islamic faith that were unfamiliar to me , particularly regarding sacred burial customs. America is a remarkably diverse place. Our nation’s diversity is its strength. As global citizens we must actively pursue experiences that broaden our individual and collective understanding of one another . Sadly many of our citizens balk at learning about others customs and beliefs. It therefore becomes easier to demonize and cast those not sharing the majority’s beliefs and practices as so called “others” even when the “other” represents over a billion human beings on the planet. Many great musicians and friends paid their respects to the Texas born guitarist. They represented every creed : Jews, Muslims, Christians, race, gender and nationality. Melvin's new band consists of young white musicians whose love and devotion for this gentle soul was apparent, Sparks is regarded as one who helped pioneer the genre known as Acid Jazz. Band members attempted to hold back tears of grieve when sharing memories and amusing stories of long hours traveling on the road together. The guitarist and band leader’s impact on his young charges was highlighted in terms of his being caring but stern father figure. He was described as a wonderful mentor, teacher and wise disciplinarian. Recalling their leader as one infused with a joy for life, love of music and friendship proved too over whelming . Their tears flowed as the audience listened but ceased after a vibrant musical jam session and repast in celebration of Melvin’s remarkable life .

Melvin never seemed to wear his faith on his sleeve, he lived it with a generous and buoyant spirit. Having known and gigged with Melvin over the years, I’m hopeful and believe that racial and religious tolerance are achievable. He left a fine example for his fellow Muslims, and Non- Muslims alike to immulate in terms of learning to respect and value others solely on the basis of the content of their character.

At the repast, I was privileged to sing with Nathan Lucas the wonderful Hammond B3 organist and a fine trio anchored by drummer, Jessie "Cheese" Hamin before an appreciative gathering of family, artists and hosts of friends. It was a beautiful home going celebration. RIP

Sunday, February 13, 2011

Roots Will Endure by Dennis Day

During the coldest week of the winter, a reported 130 million Americans viewed the ABC-TV dramatization “Roots” and were led to reflect in their cozy living rooms on the barbarous conditions that were imposed on blacks under chattel slavery.

Now efforts are afoot to discredit not only the grand patriarch of “Roots” – Kunta Kinte – but also the literary judgment of his grandson four times removed, Alex Haley, the book’s author.

Thanks to reporter Mark Ottoway of the London Times, who went sleuthing in the Gambian village where Haley sought his ancestral fathers, a remarkable feat of genealogical detective work is being questioned on its merits as a historical narrative.

Ottoway’s attempt to debunk the book could have a depressing effect on Juffure, the Gambian village where Kunta Kinte grew up. As a result of Haley’s narrative, the village is becoming a tourist attraction. But more is at stake in the “Roots” controversy than the economic fortunes of an African village, as important as they are.

Ottoway’s dig at the roots of “Roots” smacks of sensationalism; of a desire to unmask the book as more fantasy than fact. But his effort to reduce Haley’s chronicle to a mere myth won’t alter the symbolic truth behind the people and events depicted by Haley. “Roots” will not wither nor die.

Ottoway is within his rights to challenge, question, and seek the truth. Sound investigative journalism helped shed light on the Watergate fiasco for Americans. Yet it somehow seems absurd that a work that took over 12 years to complete should face a serious challenge from a reporter whose counter-intelligence efforts took an estimated nine days.

Ottoway’s main charge is that, in his eagerness to discover his African ancestors, Haley was the victim of a bogus “griot,” or village historian. The Britisher claims that, having been apprised of Haley’s quest beforehand, the griot obliged with “facts” to fit Haley’s dream.

Ottoway, in short, asserts that Haley learned of Kunta Kinte from a man of “notorious unreliability.” Yet cultural anthropologists have long valued the accounts of “griots” in cultures in which oral history flourishes. Village griots are not to be confused with village idiots. In cultures that rely on oral history, they have a position of real trust and status.

One should not forget that Haley’s search for his African roots began with cherished stories about “the defiant African” that were told by Haley’s relatives on balmy southern nights in Henning, Tennessee.

After diligent searching through plantation records, Haley was able to fill in most of the details of the American lives that preceded his. With the help of a linguistic expert in 1967, Haley traced his bloodline in Gambia through three African words that were used commonly and idiomatically among the villagers of Gambia.

Haley must have known how much scrutiny his book would attract, and he has offered to debate his critics on the reliability of his methods. As one who heard the author lecture in 1974 at a Midwestern college, prior to the publication of “Roots” my single most lasting impression was of the precision and consummate dedication that Haley was investing in the completion of his genealogical mosaic.

The Mark Ottoways of the world will undoubtedly persist, by their own lights, with the same sort of tenacity – and no doubt there will be critics of the critics.

As the critics attempt to uproot “Roots,” however, the sad thing will be their lack of facility in sorting out the forest from the trees. Despite minor technical flaws that some historians have found in “Roots,” the spirit of Kunta Kinte’s epic will prevail and its importance as a human chronicle will stand as tall as the California redwoods.

(Dennis Day is a supervisor in the Division of School Extension of the Philadelphia School District.)